When we say the word game in the context of AI we usually don’t mean it in the sense of entertainment games, instead we refer to a more general definition of a game:

A game is a multi-agent environment in which agents compete and/or cooperate on some specific task(s) while meeting some specific criteria. An agent is referred to as a player.

With this general definition we could see that a situation, like driving your car to a specific place, is a game. In such a situation, you (as a player) exist in an environment along with other drivers (other players) and you cooperate with some drivers to avoid crashes and reach your destination and compete with other drivers to reach there fast.

We can easily see that entertainment games also fall under the general definition of games. Take chess for example. In chess there are two players (multi-agent) who are competing on who captures the other’s king first (the task) in the lowest number of moves (the criteria).And because entertainment games have the same properties and characteristics of any other general game, we can use a simple entertainment game to demonstrate the AI concepts and techniques used in any form of a general game, and that’s what this post is all about.

We’ll be working with Tic-Tac-Toe as our demonstration game mainly because of its simplicity. It has simple rules, simple actions, and simple ending configurations, which makes it easy to describe it computationally.

At the end of this post, you should have a working Tic-Tac-Toe game like the one here. I’ll be focusing entirely on the game representation code and the AI code. I’ll not talk about any UI code or any of the tests code, but these are fully commented and easy to understand when read. The whole project including the tests is available at Github.

The first thing we need to do is to describe and understand the game we want to build. We could describe it verbally as follows:

Two players (player X, and player O) play on 3x3 grid. Player X is a human player, and player O is an AI. A player can put his/her letter (either X or O) in an empty cell in the grid. If a player forms a row, a column or a diagonal with his/her letter, that player wins and the game ends. If the grid is full and there’s no row, column or diagonal of the same letter, the game ends at draw. A player should try to win in the lowest possible number of moves.

Formal Definition

In working on an AI problem, one of the most fundamental tasks is to convert a verbal description of the problem into a formal description that can be used by a computer. This task is called Formal Definition. In formal definition we take something like the verbal description of Tic-Tac-Toe we wrote above, and transform it into something we can code. This step is extremely important bacause the way you formally define your problem will determine whether easy or difficult it will be to implement the AI that solves the problem, and we certainly want that to be easy.

Usually, there are some ready definitions we can use and tweak in formally defining a problem. These definitions have been presented and accepted by computer scientists and engineers to represent some classes of problems. One of these definitions is the game definition: If we know our problem represents a game, then we can define it with the following elements:

- A finite set of states of the game. In our game, each state would represent a certain configuration of the grid.

- A finite set of players which are the agents playing the game. In Tic-Tac-Toe there’s only two players: the human player and the AI.

- A finite set of actions that the players can do. Here, there’s only one action a player can do which is put his/her letter on an empty cell.

- A transition function that takes the current state and the played action and returns the next state in the game.

- A terminal test function that checks if a state is terminal (that is if the game ends at this state).

- A score function that calculates the score of the player at a terminal state.

Using this formal definition, we can start reasoning about how we’re gonna code our description of the game into a working game:

The State

As we mentioned, one of the elements of our game is a set of states, so we now need to start thinking about how we’re gonna represent a state computationally.

We said earlier that a state would represent a certain configuration of the grid, but this information need to be associated with some other bookkeeping. In a state, beside knowing the board configuration, we’ll need to know who’s turn is it, what the result of the game at this state is (whether it’s still running, somebody won, or it’s a draw), and we’ll need to know how many moves the O player (AI player) have made till this state (you would think that we’ll need to keep track of X player moves too, but no, and we’ll see soon why).

The easiest way to represent the state is to make a class named State from which all the specific states will be instantiated. As we’ll need to read and modify all the information associated with a state at some points, we’ll make all the information public. We can see that modifying X moves count, the result of the state, and the board can be done with a simple assignment operation; while on the other hand, modifying the turn would require a comparison first to determine if it’s X or O before updating it’s value. So for modifying the turn, we’ll use a little public function that would do this whole process for us.

There are still two more information we would need to know about a state. The 1st one is the empty cells in the board of this state. This can be easily done with a function that loops over the board, checks if a cell has the value “E” (Empty) and returns the indices of these cells in an array. The second information we need to know is that if this state is terminal or not (the terminal test function). This also can be easily done with a function that checks if there are matching rows, columns, or diagonals. If there is such a configuration, then it updates the result of the state with the winning player and returns true. If there is no such thing, it checks if the board is full. If it’s full, then it’s a draw and returns true, otherwise it returns false.

For the board, it would be simpler to represent it as a 9-elements one-dimensional array instead of a 3x3 two-dimensional one. The 1st three elements would represent the 1st row, the 2nd three for the 2nd row, and the 3rd three for the 3rd row. One last thing to worry about is how we can construct a state. Instead of at each time we construct a state form scratch and fill its information one by one (think about filling the board array element by element), it would be convenient if we have a copy-constructor ability to construct a new state from an old one and have minimal information to modify.

Now we’re ready to write our State class:

/*

* Represents a state in the game

* @param old [State]: old state to intialize the new state

*/

var State = function(old) {

/*

* public : the player who has the turn to player

*/

this.turn = "";

/*

* public : the number of moves of the AI player

*/

this.oMovesCount = 0;

/*

* public : the result of the game in this State

*/

this.result = "still running";

/*

* public : the board configuration in this state

*/

this.board = [];

/* Begin Object Construction */

if(typeof old !== "undefined") {

// if the state is constructed using a copy of another state

var len = old.board.length;

this.board = new Array(len);

for(var itr = 0 ; itr < len ; itr++) {

this.board[itr] = old.board[itr];

}

this.oMovesCount = old.oMovesCount;

this.result = old.result;

this.turn = old.turn;

}

/* End Object Construction */

/*

* public : advances the turn in a the state

*/

this.advanceTurn = function() {

this.turn = this.turn === "X" ? "O" : "X";

}

/*

* public function that enumerates the empty cells in state

* @return [Array]: indices of all empty cells

*/

this.emptyCells = function() {

var indxs = [];

for(var itr = 0; itr < 9 ; itr++) {

if(this.board[itr] === "E") {

indxs.push(itr);

}

}

return indxs;

}

/*

* public function that checks if the state is a terminal state or not

* the state result is updated to reflect the result of the game

* @returns [Boolean]: true if it's terminal, false otherwise

*/

this.isTerminal = function() {

var B = this.board;

//check rows

for(var i = 0; i <= 6; i = i + 3) {

if(B[i] !== "E" && B[i] === B[i + 1] && B[i + 1] == B[i + 2]) {

this.result = B[i] + "-won"; //update the state result

return true;

}

}

//check columns

for(var i = 0; i <= 2 ; i++) {

if(B[i] !== "E" && B[i] === B[i + 3] && B[i + 3] === B[i + 6]) {

this.result = B[i] + "-won"; //update the state result

return true;

}

}

//check diagonals

for(var i = 0, j = 4; i <= 2 ; i = i + 2, j = j - 2) {

if(B[i] !== "E" && B[i] == B[i + j] && B[i + j] === B[i + 2*j]) {

this.result = B[i] + "-won"; //update the state result

return true;

}

}

var available = this.emptyCells();

if(available.length == 0) {

//the game is draw

this.result = "draw"; //update the state result

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

};

};

The Human Player

We move on to the next element of our definition, which is the players. Our first player will be the human player, which we will represent and implement along with its actions through the UI and its controls. We won’t dive into that like we said earlier, but it’s very easy to understand by reading the code directly; it’s basically a jQuery click event handler on the grid cells that reads the current game state and update it by the performed move. You can read it off the control.js file in the repo.

The AI Player

We now turn to the AI player. Usually when we design an AI, we would want it to be able to take the best possible decision on the problem at hand, but as we’re designing an AI for an entertainment game, I’d like to take advantage of that and demonstrate something related to entertainment game AI, which is the multiple difficulty levels. We’ll be designing an AI that can play Tic-Tac-Toe at three difficulty levels: Blind level in which the AI understands nothing about the game, Novice level in which the AI plays the game as a novice player, and the Master level in which the AI plays the game like a master you can never beat no matter how much you tried (go ahead, play with master and see for yourself).

We’ll postpone the detailed implementation of the AI a little bit. We’ll focus now on the internal structure of the AI class we’ll use to create the AI players. An AI player needs to know the following: its intelligence level (which is the game’s difficulty level), and the game it plays. We can represent those as private attributes and pass the intelligence level to the constructor and create a little public setter function that attaches the AI player to the game it plays. The AI player will need to be able to reason about the decisions it make which is the core functionality of the AI, we’ll implement that with a private function we name minimaxValue (don’t worry, we’ll get to what that means soon. All you need to know now is that it’s a function that takes a state and returns a number). The AI will also need to be able take three types moves: a blind move, a novice move, and a master move; we can implement that with a private function for each. The last thing we need is a way to notify the AI when its turn comes up to the action appropriate to its intelligence level, this can be simply done with a public function we call notify.

Our AI class would be something like this:

/*

* Constructs an AI player with a specific level of intelligence

* @param level [String]: the desired level of intelligence

*/

var AI = function(level) {

//private attribute: level of intelligence the player has

var levelOfIntelligence = level;

//private attribute: the game the player is playing

var game = {};

/*

* private recursive function that computes the minimax value of a game state

* @param state [State] : the state to calculate its minimax value

* @returns [Number]: the minimax value of the state

*/

function minimaxValue(state) { ... }

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a blind move

* that is: choose the cell to place its symbol randomly

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeABlindMove(turn) { ... }

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a novice move,

* that is: mix between choosing the optimal and suboptimal minimax decisions

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeANoviceMove(turn) { ... }

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a master move,

* that is: choose the optimal minimax decision

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeAMasterMove(turn) { ... }

/*

* public method to specify the game the ai player will play

* @param _game [Game] : the game the ai will play

*/

this.plays = function(_game){

game = _game;

};

/*

* public function: notify the ai player that it's its turn

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

this.notify = function(turn) {

switch(levelOfIntelligence) {

//invoke the desired behavior based on the level chosen

case "blind": takeABlindMove(turn); break;

case "novice": takeANoviceMove(turn); break;

case "master": takeAMasterMove(turn); break;

}

};

};

The AI Actions

To simpilfy the code for the AI decision making and moves, we can take the code that represents the available actions that the AI have and will reason about to another class outside the AI class. As we just said, it would simpler and better modular design for the project.

We’ll need the AI action to hold two information: the position on the board that it’ll make its move on (remember that it’s a one-dimensional array index) and the minimax value of the state that this action will lead to (remember the minimax function ?). This minimax value will be the criteria at which the AI will chose its best available action. It won’t do any harm if we implemented the transition function into the action itself by making a public function that takes the current state, apply the action to it, and return the next state.

Our AI action class would look like this:

/*

* Constructs an action that the ai player could make

* @param pos [Number]: the cell position the ai would make its action in

* made that action

*/

var AIAction = function(pos) {

// public : the position on the board that the action would put the letter on

this.movePosition = pos;

//public : the minimax value of the state that the action leads to when applied

this.minimaxVal = 0;

/*

* public : applies the action to a state to get the next state

* @param state [State]: the state to apply the action to

* @return [State]: the next state

*/

this.applyTo = function(state) {

var next = new State(state);

//put the letter on the board

next.board[this.movePosition] = state.turn;

if(state.turn === "O")

next.oMovesCount++;

next.advanceTurn();

return next;

}

};

We said above that the AI uses the minimax value to choose the best action from a list of available actions, so it’s very reasonable to think that we’d need some way to sort the actions based on their minimax values. For that, we provide two public static functions that we can use as a compare function to pass to the javascript’s Array.prototype.sort function to sort the list of actions in both ascending and descending manners.

/*

* public static method that defines a rule for sorting AIAction in ascending manner

* @param firstAction [AIAction] : the first action in a pairwise sort

* @param secondAction [AIAction]: the second action in a pairwise sort

* @return [Number]: -1, 1, or 0

*/

AIAction.ASCENDING = function(firstAction, secondAction) {

if(firstAction.minimaxVal < secondAction.minimaxVal)

return -1; //indicates that firstAction goes before secondAction

else if(firstAction.minimaxVal > secondAction.minimaxVal)

return 1; //indicates that secondAction goes before firstAction

else

return 0; //indicates a tie

}

/*

* public static method that defines a rule for sorting AIAction in descending manner

* @param firstAction [AIAction] : the first action in a pairwise sort

* @param secondAction [AIAction]: the second action in a pairwise sort

* @return [Number]: -1, 1, or 0

*/

AIAction.DESCENDING = function(firstAction, secondAction) {

if(firstAction.minimaxVal > secondAction.minimaxVal)

return -1; //indicates that firstAction goes before secondAction

else if(firstAction.minimaxVal < secondAction.minimaxVal)

return 1; //indicates that secondAction goes before firstAction

else

return 0; //indicates a tie

}

The Game

This is the structure that will control the flow of the game and glue everything together in one functioning unit. In such a structure, we’d like to keep and access three kinds of information : the AI player who plays the game with the human, the current state of the game, and the status of the game (whether it’s running or ended), we’ll keep those as public attributes for easy access. We’d also need a way to move the game from one state to another as the playing continues, we can implement that with a public function that advances the game to a given state and checks if the game ends at this state and what is the result, if the game doesn’t end at this state, the function notifies the player who plays next to continue. Finally, we’d need a public function to start the game.

/*

* Constructs a game object to be played

* @param autoPlayer [AIPlayer] : the AI player to be play the game with

*/

var Game = function(autoPlayer) {

//public : initialize the ai player for this game

this.ai = autoPlayer;

// public : initialize the game current state to empty board configuration

this.currentState = new State();

//"E" stands for empty board cell

this.currentState.board = ["E", "E", "E",

"E", "E", "E",

"E", "E", "E"];

this.currentState.turn = "X"; //X plays first

/*

* initialize game status to beginning

*/

this.status = "beginning";

/*

* public function that advances the game to a new state

* @param _state [State]: the new state to advance the game to

*/

this.advanceTo = function(_state) {

this.currentState = _state;

if(_state.isTerminal()) {

this.status = "ended";

if(_state.result === "X-won")

//X won

ui.switchViewTo("won");

else if(_state.result === "O-won")

//X lost

ui.switchViewTo("lost");

else

//it's a draw

ui.switchViewTo("draw");

}

else {

//the game is still running

if(this.currentState.turn === "X") {

ui.switchViewTo("human");

}

else {

ui.switchViewTo("robot");

//notify the AI player its turn has come up

this.ai.notify("O");

}

}

};

/*

* starts the game

*/

this.start = function() {

if(this.status = "beginning") {

//invoke advanceTo with the intial state

this.advanceTo(this.currentState);

this.status = "running";

}

}

};

Let’s Do Some AI

It certainly feels like a long way from the beginning of the post till this point where we start working on the AI. This reflects how important is the formal definition phase along with planning and designing your modules and how they’re gonna talk to each other and work together. These phases are a lot of work, and some of this work could be boring, but when done right we’ll find ourselves at this point only worrying about the good stuff: the reasoning, the math, and the algorithms.

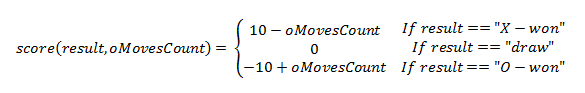

The Score Function

We now take the first step in implementing our AI, which is implementing the score function. The score function is the way the AI can know the benefit of a specific action it can take. Basically, the AI will be asking itself through the minimaxValue function : “Is this action is getting me a high score or a low score ?”.

So how can we calculate the score at a terminal state ?!

Well, form our verbal description of the game we can see that the score is affected by two factors: the player winning or losing, and the number of moves the player makes to win. We make the AI’s job is to worsen X player’s life as much as possible. So we need to design a score function that makes O take decisions that results in X having as low score as possible.

You might ask a question here: now the AI’s job is to annoy the X player and make him lose score, would that mean that the AI wouldn’t work to gain score itself ? Is it just going to be something with a grudge against the X player ?!

Actually, the AI will be trying to make itself win by making X’s life hell. So it kills two birds with one stone !

The reason behind this is that Tic-Tac-Toe is a game of a special kind, a kind called zero-sum games. In this type of games, the scores of all players sum to 0, which means that in a two-players game the score of one player is negative of the score of the other player, so if player 1 gets a score of 5 then player 2 gets a score of -5, making the sum of all scores to be 5 + (-5) = 0, hence : zero-sum game. Zero-sum games are pure competition games, there’s no cooperation of any kind between the players.

Because Tic-Tac-Toe is a zero-sum game, the AI can spend all its life minimizing X’s score and at the same time be maximizing its score.

So now we can design a score function that only calculates the score of X at a terminal state. If the AI plays with X (which is something that’s gonna occur in the tests), it can work on maximizing its value. On the other hand, If the AI plays with O (which is the case here), it works on minimizing its value.

We can reason about such function in the following manner:

- If X wins, we give him a score of 10 (just an arbitrary value), but O (the AI) shouldn’t make this easy to happen, it must fight, it shouldn’t surrender when it sees that it’s going to lose. So the AI should make as much moves as possible to force the X player to make more moves to win. So the total score for X should be : 10 - oMovesCount.

- If X loses, we give him a score of -10, and O should get to this state with the least possible number of moves while still making X’s score as low as possible. So we penalize any increase in the number of O moves by an increase in X’s score. So the total score for X should be : -10 + oMovesCount

- If the game is a draw, X’s total score should be : 0

We now have our score function (which doesn’t need to keep track of X’s moves count as we said before):

We’ll implement this as a public static function of the Game class. We implement it in the Game class because it’s a game-related information, and static because it doesn’t depend on specific instances of the game.

/*

* public static function that calculates the score of the x player in a terminal state

* @param _state [State]: the state in which the score is calculated

* @return [Number]: the score calculated for the human player

*/

Game.score = function(_state) {

if(_state.result !== "still running") {

if(_state.result === "X-won"){

// the x player won

return 10 - _state.oMovesCount;

}

else if(_state.result === "O-won") {

//the x player lost

return -10 + _state.oMovesCount;

}

else {

//it's a draw

return 0;

}

}

}

The Minimax Algorithm

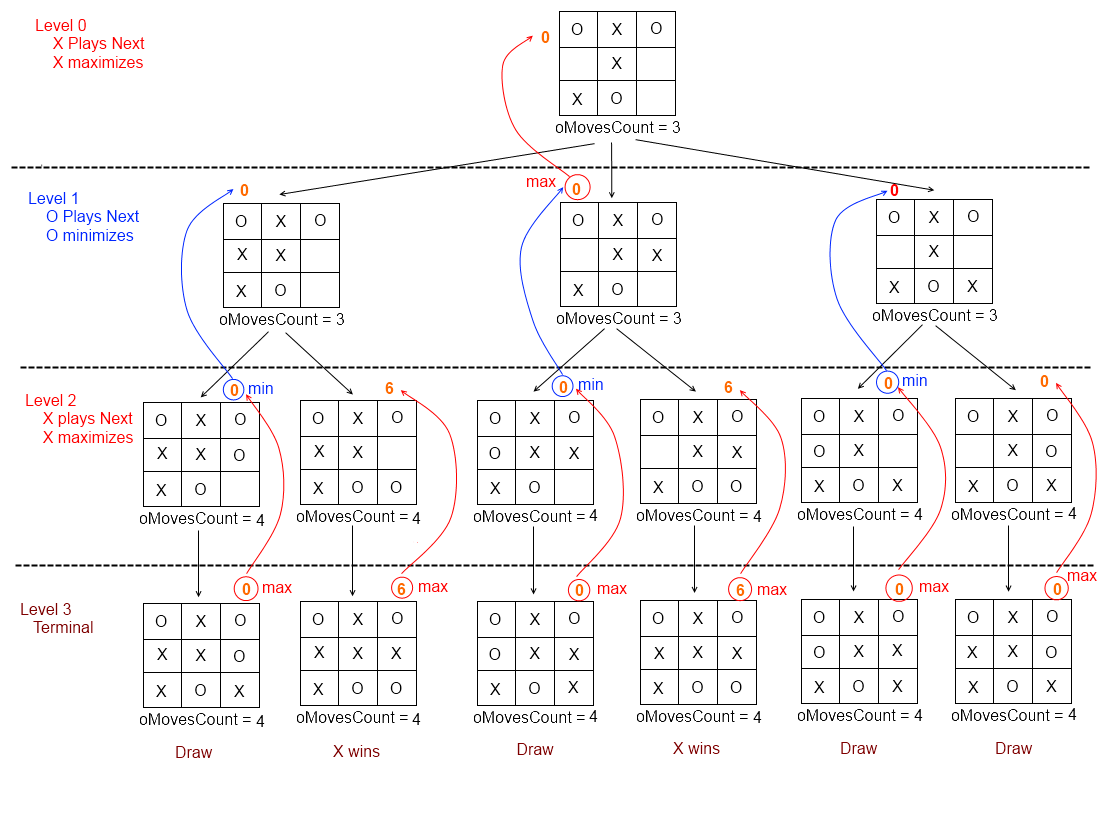

Now the AI needs a way to use the information provided by the score function in making an optimal decision, and this is where minimax comes to help. The Basic intuition behind the minimax decision algorithm is that at a given state, the AI will think about the possible moves it can make, and about the moves the opponent can make after that. This process continues until terminal states are reached (not in the actual game, but in the AI’s thought process). The AI then chooses the action that leads to the best possible terminal state according to its score.

The algorithm is used to calculate the minimax value of a specific state (or the action that leads to that state), and it works by knowing that someone wants to minimize the score function and the other wants to maximize the score function (and that’s why it’s called minimax). Suppose that O wants to calculate the minimax value of the action that leads it to the state at level 0 in the following figure:

- At Level 0: O wants to calculate the minimax value of that state, So it asks a question: What are X’s moves if I took the action to that state ?! To answer this question, it generates all the states that X can reach through all his possible actions (The states in Level 1).

- At Level 1: O Thinks about the moves it can make in response to each of X’s moves, so it generates all the states it can reach from there by all possible actions (The states in Level 2).

- At Level 2: Having all the states it can reach, O keeps thinking ahead and considers all of X’s moves he can take from there, so it generates all the states that X can reach through all his possible actions (The Terminal States).

- At Level 3 (Terminal States): O now knows how the game could end, it knows all the possible configurations that the game could end into and have a tree with all the possible paths it could take (the tree in the figure).

O now uses the score function to calculate the score of each terminal state it can reach (the orange numbers above each state in the figure). After that, it starts climbing the tree up to the root state ,which is the state we started off to calculate its minimax value.

- At Level 2: O knows that X is the one playing next at this level. It also knows that at each possible state at this level, X will choose to go to the child state (at Level 3) with the largest score. So O backs up the minimax value of each state at Level 2 with the maximum score of its child states.

- At Level 1: O knows that it’s its turn to play at this level. It wants to choose a child state (from Level 2) that makes X’s score as low as possible. So O backs up the minimax value of each state at level 1 with the minimumm minimax value of its child states.

- At Level 0: O follows the same reasoning it followed at level 2. It backs up the minmax value of the root state with the maximum minimax value of its child states (the ones at level 1).

The algorithm now terminates and returns the minimax value of the desired state to be 0.

It now obvious that the minimax algorithm is a recursive algorithm and its base case is reaching a terminal state. We can implement it with a recursive function that recurs down to the terminal states, and backs up the minimax value as the recursion unwinds.

/*

* private recursive function that computes the minimax value of a game state

* @param state [State] : the state to calculate its minimax value

* @returns [Number]: the minimax value of the state

*/

function minimaxValue(state) {

if(state.isTerminal()) {

//a terminal game state is the base case

return Game.score(state);

}

else {

var stateScore; // this stores the minimax value we'll compute

if(state.turn === "X")

// X maximizs --> initialize to a value smaller than any possible score

stateScore = -1000;

else

// O minimizes --> initialize to a value larger than any possible score

stateScore = 1000;

var availablePositions = state.emptyCells();

//enumerate next available states using the info form available positions

var availableNextStates = availablePositions.map(function(pos) {

var action = new AIAction(pos);

var nextState = action.applyTo(state);

return nextState;

});

/* calculate the minimax value for all available next states

* and evaluate the current state's value */

availableNextStates.forEach(function(nextState) {

var nextScore = minimaxValue(nextState); //recursive call

if(state.turn === "X") {

// X wants to maximize --> update stateScore iff nextScore is larger

if(nextScore > stateScore)

stateScore = nextScore;

}

else {

// O wants to minimize --> update stateScore iff nextScore is smaller

if(nextScore < stateScore)

stateScore = nextScore;

}

});

//backup the minimax value

return stateScore;

}

}

A Master Move

Now it’s time to take some decisions. Using the minimax algorithm, taking an optimal decision is a trivial process:

- Enumerate all the possible action that could be taking.

- Calculate the minimax value of each action (that is the minimax value of the state that each action leads to).

- If X is the one who is taking the decision: choose the action with the maximum minimax value. Go to 5.

- If O is the one who is taking the decision: choose the action with the minimum minimax value. Go to 5.

- Carry out the chosen action.

A player who always plays the optimal move is by no doubt a master player. So we implement our takeAMasterMove function to allow the AI to always choose the optimal action. This the most difficult level of the game, as it can be proven that a player that plays optimally all the time cannot lose. Your best chance at this level is leading the game to a draw, otherwise you’ll lose.

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a master move,

* that is: choose the optimal minimax decision

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeAMasterMove(turn) {

var available = game.currentState.emptyCells();

//enumerate and calculate the score for each avaialable actions to the ai player

var availableActions = available.map(function(pos) {

var action = new AIAction(pos); //create the action object

//get next state by applying the action

var next = action.applyTo(game.currentState);

//calculate and set the action's minmax value

action.minimaxVal = minimaxValue(next);

return action;

});

//sort the enumerated actions list by score

if(turn === "X")

//X maximizes --> descend sort the actions to have the largest minimax at first

availableActions.sort(AIAction.DESCENDING);

else

//O minimizes --> acend sort the actions to have the smallest minimax at first

availableActions.sort(AIAction.ASCENDING);

//take the first action as it's the optimal

var chosenAction = availableActions[0];

var next = chosenAction.applyTo(game.currentState);

// this just adds an X or an O at the chosen position on the board in the UI

ui.insertAt(chosenAction.movePosition, turn);

// take the game to the next state

game.advanceTo(next);

}

A Novice Move

A Novice player is a player who sometimes takes the optimal move and some other time he takes a sub-optimal move. We could model that with a probability, like saying that it takes the optimal move 40% of the time and the sub-optimal move 60% of the time.

Coding a probability might seem like a challenging task if you didn’t do it before (at least it did to me), but it turns out that it’s a very simple task : If you want to execute a statement P percent of the time, just generate a random number between 0 and 100. You only execute that statement if the generated random number is less than or equal to P.

var P = 40; //some probability in percent form

if(Math.random()*100 <= P) {

// carry out the probable task with probability P

}

else {

// carry out the other probable task with probability 1 - P

}

Probabilities and randomness is the way used in most entertainment games to make the games playable and with some variance in the AI actions during the game. Imagine playing Call of Duty with an AI that manages to always make headshots with no misses at all, such a game wouldn’t be playable and unrealistic. This is where probability comes and add some small probablity that the AI headshots, with a large probability for regular shots and misses. In our game, we’ll use probablity to make the AI miss the optimal move for 60% of the time, and make it for 40% of the time.

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a novice move,

* that is: mix between choosing the optimal and suboptimal minimax decisions

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeANoviceMove(turn) {

var available = game.currentState.emptyCells();

//enumerate and calculate the score for each available actions to the ai player

var availableActions = available.map(function(pos) {

var action = new AIAction(pos); //create the action object

//get next state by applying the action

var nextState = action.applyTo(game.currentState);

//calculate and set the action's minimax value

action.minimaxVal = minimaxValue(nextState);

return action;

});

//sort the enumerated actions list by score

if(turn === "X")

//X maximizes --> decend sort the actions to have the maximum minimax at first

availableActions.sort(AIAction.DESCENDING);

else

//O minimizes --> ascend sort the actions to have the minimum minimax at first

availableActions.sort(AIAction.ASCENDING);

/*

* take the optimal action 40% of the time

* take the 1st suboptimal action 60% of the time

*/

var chosenAction;

if(Math.random()*100 <= 40) {

chosenAction = availableActions[0];

}

else {

if(availableActions.length >= 2) {

//if there is two or more available actions, choose the 1st suboptimal

chosenAction = availableActions[1];

}

else {

//choose the only available actions

chosenAction = availableActions[0];

}

}

var next = chosenAction.applyTo(game.currentState);

ui.insertAt(chosenAction.movePosition, turn);

game.advanceTo(next);

};

A Blind Move

We assume that a blind player is a player who doesn’t know anything about the game and doesn’t have the ability to reason about the which action is the better than the other. A blind player chooses his actions randomly all the time, and this is the easiest level of the game.

/*

* private function: make the ai player take a blind move

* that is: choose the cell to place its symbol randomly

* @param turn [String]: the player to play, either X or O

*/

function takeABlindMove(turn) {

var available = game.currentState.emptyCells();

var randomCell = available[Math.floor(Math.random() * available.length)];

var action = new AIAction(randomCell);

var next = action.applyTo(game.currentState);

ui.insertAt(randomCell, turn);

game.advanceTo(next);

}

How difficult is each difficulty ?

We know that the master level is the hardest level in the game. We can easily say that because, as we mentioned earlier, it can be formally proven that a player playing optimally all the time cannot lose.

But can we make the same statements about each of the other two levels, can we say that the novice level is harder than the blind level ?!

We can informally say that becuase the novice player has some understanding of the game and knows how to reason about the game, it’s a better player than a blind one who understands nothing about the game and doesn’t know how to reason about it. So, informally, Novice level is harder than blind level.

Formally asserting that statement about the novice and blind levels can be difficult and cumbersome because of the probability and randomness involved in both levels, but we can assert it statistically. A good idea is to have a lot of games (say 1000) played against each of the two levels and count the number of games won (in 3, 4 and 5 moves), and the number of games lost in both cases. We then see what these data tell us. A very bad idea is to play the 1000 games yourself !

This is where the code in tests come in. Without getting into the detailed implementation , the idea is two make two AIs play 1000 games against each other and automatically collect the data we specified above. This is much faster and efficient than playing the 1000 games yourself.

The following chart represents the data about a novice X player’s results in 1000 games against a blind O player, and 1000 games against a novice O player.

From the chart we can see that when playing with novice, the number of wins in 3 and 4 moves are getting smaller while the number of wins in 5 moves gets higher. This means that it’s more difficult for X to win in low number of moves when playing with novice than playing with blind. Moreover, the number of lost and draw games gets higher while playing against novice, which means that it’s harder for X to win while playing against novice than playing against blind. All this statistically tell us the novice is indeed harder than blind.

Phew !

We Finally come to the end of this. It was a long ride. I tried to not cover only the AI work, but the whole process of developing a working AI application. You should now be able to build the project successfully, and I strongly suggest that you try and apply the same reasoning (or make better reasoning) on other games. Remember that the whole project is on this Github repo.

Thanks for reading !

Comments