Introduction

In Part 1 we talked about the challenges we could face in doing iterative asynchronous work, and we devised two patterns that we could use to overcome these challenges. Now we turn our attention to the challenges that we would encounter in trying to achieve recursion of asynchronous operations and how we could overcome them. As in the last time, we start our discussion with an example problem to work on, then we investigate the possible solutions.

Problem 2

You and your team are creating a module system for your little organization (something that’s very similar to npm, but private to your organization). The system should be able to load a module on demand from a shared organization server. Each module can have at most one other module as a dependency, and when a module is fetched, its dependency and its dependency’s dependency (and so on…) should be fetched as well to ensure that the module will work correctly. Your task now is to write a script that runs before downloading the module that queries the metadata of the module on the server to determine the list of all modules and dependencies that you’ll need to download. All modules metadata reside on the route “/meta/{module_name}”, and it should be retrieved using a GET request. Each request returns a JSON response with at most two fields: “hasDependency” that is true if the module has a dependency, false otherwise; and “dependency” which contains the name of the dependency module if exists.

In this gist you’ll find a sample node http server that you can run locally to mimic the behaviour of the shared organization server described in the problem. Just open the terminal in the containing folder and run it with node server. The server should then be accessible at http://localhost:8080.

Reasoning about a Solution

The first step we could take to tackle this problem is to create a function that can load the metadata a single module from the server. This function (let’s call it loadMetaOf) is very simple; it takes two arguments: the name of the module we want to load its metadata, and an array that represents the list of all modules that will need to be loaded. This function initiates a GET request to the server to retrieve the module’s metadata and appends its name to the list when the response comes.

From the problem’s description, it’s obvious that we’re gonna need to call this function many times to retrieve all the dependencies, but unfortunately we don’t know how many times! This is because that we wouldn’t know that we’ll need to call the function with another module unless we get the response from the previous call and it indicated that there’s a dependency that needs to be loaded. So we won’t be able to use simple iterations like those we worked with in part 1.

A straightforward solution ,to our ignorance of how many times we’re gonna need to call the function, is recursion. We can make our function recursive, so that it would call itself again if the response indicated a dependency, or return if no dependency is indicated.

A Correct, yet Imaginary, Synchronous Solution

Continuing with the tradition we started in part 1, we begin first with a synchronous approach to the solution we just devised. But unfortunately, node doesn’t have a synchronous version for its http module (unlike the filesystem fs module we used in part 1). So let’s for now imagine that next to node’s asynchronous http.get method, there’s a synchronous version called http.getSync that takes the request url and returns the response body as a string.

A correct, yet imaginary, implementation of our solution above would go like this:

var http = require('http');

function loadMetaOf(name, list) {

var response = http.getSync('http://localhost:8080/meta/' + name);

var jsonResponse = JSON.parse(response); // we parse the response string to JSON

list.push(name); // append the module name to the list logged to the user later

if(jsonResponse.hasDependency) {

loadMetaOf(jsonResponse.dependency, list)

return; // this is useless, but we need here for our discussion

}

else {

return; // this is also useless

}

}

var list = [];

loadMetaOf('moduleA', list);

// log the details to the user

console.log('fetched all metadata for moduleA');

console.log('all of the following modules need to be loaded');

console.log(list);

Can we now use the real http.get asynchronous method instead of the imaginary synchronous version and get a correct asynchronous solution?!

A Wrong Asynchronous Solution

var http = require('http');

function loadMetaOf(name, list) {

http.get('http://localhost:8080/meta/' + name, function(response) {

var responseBody = ""; // will hold the response body as it comes

// join the data chuncks as they come

response.on('data', function(chunck) { responseBody += chunck });

response.on('end', function() {

var jsonResponse = JSON.parse(responseBody);

list.push(name);

if(jsonResponse.hasDependency) {

loadMetaOf(jsonResponse.dependency, list);

return; // this is useless, but we need here for our discussion

}

else {

return; // this is also usless

}

});

});

}

var list = [];

loadMetaOf('moduleA', list);

// log the details to the user

console.log('fetched all metadata for moduleA');

console.log('all of the following modules need to be loaded');

console.log(list);

Whenever you run this script you’re gonna get an empty list of modules instead of a populated list of three modules. So what’s the problem?!

The problem is that the usual idea we have about recursion doesn’t work with asynchronous calls. The usual idea we have about recursion is that execution will not go past the call loadMetaOf('moduleA', list) untill all the recursive calls within are unwound and returned, which means that all operations on list are done and it’s safe to use its value when the execution goes past the call to loadMetaOf, but this is not the case when the function involves an asynchronous call.

What happens here is that loadMetaOf doesn’t do any of the work itself, it just initiates an asynchronous http.get to retrieve the resource over the network and then returns immediately. The actual work will be started by the callback of the http.get, which won’t be invoked until the connection to the server is made. Moreover, the actual processing of the metadata won’t start until the response is fully received from the server.

By the time all this waiting to happen, the execution would have already gone past the loadMetaOf('moduleA', list) line and printed the list with its empty initial value before any work could be done on it.

A Correct Asynchronous Approach

Now let’s imagine that you’re gonna simulate this problem on a human scale. Instead of downloading a module from a remote server, you’re building a Lego structure where the parts you need are stored in several storage facilities. Each new part you acquire has an associated note about whether another part in needed and from which storage facility you can get it.

You’re the one responsible of building the structure once you have all the parts. You delegate one of your teammates to go search for the parts, you give him the first part and the associated note along with a bucket to put the parts in. Because there probably gonna be so many parts, you want have the time to review the bucket’s content when your teammate returns it, so you’re gonna blindly take it but you make him promise that he won’t return the bucket unless all the parts are there, and you know that your teammate is trustworthy and that he’s gonna keep his promise. You set your teammate off on his journey and you go back to whatever work you have until he comes back.

Your teammate wants to keep his promise to you, so he’s worried about what could go wrong that would prevent him from keeping it. He thinks that the only possible thing that would screw things up is that after he collects a part he goes back to rest for a while and in that moment you could see the bucket and take it as you think that he collected all the parts. To avoid this, he makes a promise to himself that he won’t even take a single step back along the road until he had gone all the way through and collected all the parts.

We can see that the promises your teammate made to you and to himself; they both constitute one big promise that once on the road, he won’t go a single step back until all the work is done. Pretty harsh terms, but such the burden an honorable and trustworthy man takes upon himself!

In the end, because your teammate kept all his promises, you’re now able to build the Lego structure successfully.

I guess the analogy is clear now; you resemble the javasctipt global scope and your teammate is the loadMetaOf function and its asynchronous work. Now we need to give the loadMetaOf function the ability to make promises to itself and to the global scope. Fortunately, instead of needing to solve the philosophical problem of machine’s morality, there’s a tool we can use for that!

Promises and Deferreds

Promises are a new feature introduced to javascript in ES6, they represent a way to write asynchronous code in a more synchronous way and it’s available in Node.js since v4.0, if you haven’t installed v4.0 yet (you should btw) you can use third-party implementation like q.

A Promise is essentially a representation of a value that is not available yet but will be resolved in the future. A promise is created using a function that takes two arguments: a resolve handler, and a reject handler. In this function you write your asynchronous call, and when the value you get from that call is available, you resolve the promise with that value using the resolve handler. And if any error occurs in the process, you reject the promise with that error using the reject handler.

var promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

try {

someAsyncCall(function(result) {

// the result in now available in the callback

resolve(result);

});

}

catch(error) {

reject(error);

}

});

Now you have a promise of a value, with that you have the ability to wait for that value to be resolved and then do some processing on it. This behaviour (called the thenable behaviour) is accomplished using the Promise.then method that takes two functions: the first which is called if the promise is resolved and it gets passed the resolved value, the other gets called if the promise is rejected and gets passed the rejected value (which is usually an error).

promise

.then(function(value) {

console.log("This is the result of someAsyncCall: ", value);

}, function(error) {

throw error; // rethrow the error

});

We see that the promise allowed us to simplify our asynchronous code by limiting the callback to only the report of the value, and all the processing logic of that value is separated to another block (the then block) outside the callback in a way that appears to be synchronous. How cool is that!

I’m sufficing with this short introduction to promises as it’s all what we need here. If you feel that you need more, you can always check html5rocks tutorial on promises. Now we need to talk about what Deferreds are.

A Deferred is an extended type of promise, created using Promise.defer() method that returns a new promise along with methods (.resolve and .reject) to change its state (to resolved or to rejected) when needed. As we think of a regular promise as a promise for a value, we can think of a deferred as a promise for work not yet finished. When the work is done, we call the deferred.resolve method to change the underlying promise’s state to resolved; and if there’s an error we call the deferred.reject method to change its state to rejected. We can use the underlying promise (accessed via deffered.promise) and utilize the thenable behaviour to do other work when the promised work is done.

Here’s a pseudo-example of how deferreds can be used:

/*

* this is a function that asynchronously bulk inserts several records into a db

* @param records [Array]: the records to be bulk inserted

* @returns [Promise]: a promise of the work (a.k.a. the bulk insertion) to be done

*/

function bulkInsert(records) {

// make your promise before the work starts: create the deferred

var deferred = Promise.defer();

executeAsyncBulkInsert(records, function(error) {

if(error)

// report that you couldn't keep your promise because of an error

deferred.reject(error);

else

// report that you kept and fullfilled your promise

deferred.resolve();

});

// give your promise

return deferred.promise;

}

bulkInsert()

.then(refrechView);

I guess it’s obvious by now, from the definition of deferreds and from the way I wrote the comments in the above snippet, that deferreds will be our tool to implement the asynchronous analogy we discussed earlier.

A correct Asynchronous Solution

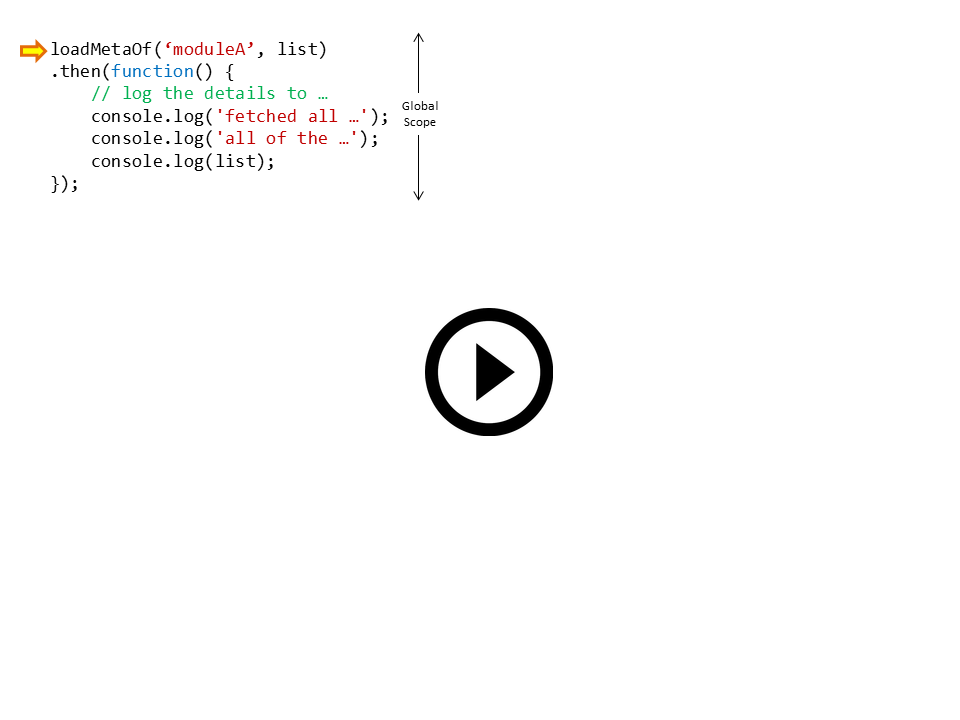

As our analogy started, our solution begins with the function loadMetaOf making a promise to the global scope. This could be done, as we saw in the above pseudo-example, by creating a deferred at the beginning of the function and returning its promise in the end. We can then take that promise in the global scope and use its then to print the logs.

So our solution would start off like this:

var http = require('http');

function loadMetaOf(name, list) {

var deferred = Promise.defer();

// here will go the function's logic

return deferred.promise;

}

var list = [];

loadMetaOf('moduleA', list)

.then(function() {

// log the details to the user

console.log('fetched all metadata for moduleA');

console.log('all of the following modules need to be loaded');

console.log(list);

});

Now we can be sure that the logs will not be printed until that promise is fulfilled. But when will that promise be fulfilled?!

In the analogy, the promise is fulfilled when the all the parts are in the bucket. So here, the promise should be fulfilled when all the module names are in the list. Refer back for a moment to the imaginary synchronous solution we made earlier; in that solution we printed the logs immediately after the global call to loadMetaOf has returned. And we know that the global call won’t return unless either there’s no dependency to get, or after the recursive call inside it has returned. In the first case we have put the module name in the list and there’s no other modules to put. And in the second case, after the recursive call inside the global call has returned, we know that the recursion had gone all the way through and went back successfully; and that means that all the modules were put in the list.

It seems now like a good idea to resolve our promise in these two cases: if there’s no dependency, and when the work in the recursive call is done. Notice that the recursive call also returns a promise that will be fulfilled when its work is done, and in its then function we should resolve our promise.

var http = require('http');

function loadMetaOf(name, list) {

var deferred = Promise.defer();

// here will go some of the function's logic

if(jsonResponse.hasDependency) {

loadMetaOf(jsonResponse.dependency, list)

.then(function() {

deferred.resolve();

});

}

else {

deferred.resolve();

}

// here will go any remainings of the function's code

return deferred.promise;

}

var list = [];

loadMetaOf('moduleA', list)

.then(function() {

// log the details to the user

console.log('fetched all metadata for moduleA');

console.log('all of the following modules need to be loaded');

console.log(list);

});

Remember in the analogy when we said that the two promises made by your teammate are actually one big promise of not to go back a single step unless all the work is done? Using this idea we can see that the way we handle our promise to the global scope implies as well the idea of the function’s promise to itself along the way. The following animation illustrates that point.

We just need now to fill in the code for the http GET request and we’ll have our working asynchronous solution!

var http = require('http');

function loadMetaOf(name, list) {

var deferred = Promise.defer();

http.get('http://localhost:8080/meta/' + name, function(response) {

var responseBody = ""; // will hold the response body as it comes

// join the data chuncks as they come

response.on('data', function(chunck) { responseBody += chunck });

response.on('end', function() {

var jsonResponse = JSON.parse(responseBody);

list.push(name);

if(jsonResponse.hasDependency) {

loadMetaOf(jsonResponse.dependency, list)

.then(function() {

deferred.resolve();

});

}

else {

deferred.resolve();

}

});

});

return deferred.promise;

}

var list = [];

loadMetaOf('moduleA', list)

.then(function() {

// log the details to the user

console.log('fetched all metadata for moduleA');

console.log('all of the following modules need to be loaded');

console.log(list);

});

Now compare this solution to the wrong asynchronous solution we worked on earlier. Remember the useless return statements there? You can see that every deferred.resolve() statement in the correct solution comes in the place of every return solution in the wrong solution (and also in the synchronous solution).

Using this observation, we can infer a pattern that we could apply not just to this problem, but to any problem that involves recursion of asynchronous work.

The “Promise not to backdown” Pattern

To write a correct recursive function that involves asynchronous work, follow these steps:

- Create a

deferredat the beginning of the function and return its promise in the end. - Between the creation and the returning of the deferred promise, write your asynchronous code.

- In the callback of your asynchronous work:

- Any code that comes after a recursive call of the function must be put inside its

thenfunction. - In the place you would write a

returnstatement if this was synchronous, put a call todeferred.resolveand pass it the returned value. - In the place you would throw an error if this was synchronous, put a call to

deferred.rejectand pass it that error.

- Any code that comes after a recursive call of the function must be put inside its

- Any code that comes after the initial call to the function must be put in its

thenfunction.

And following the steps of professor Kenneth A. Reek in his paper Design patterns for semaphores where he gave his patterns catchy names, I’ll call the pattern we inferred here the “Promise not to backdown” pattern.

Summary

In this part we explored the challenge of writing recursive functions that involve asynchronous work, and we devised the “Promise not to backdown” pattern which uses promises and deferreds to overcome this challenge. This concludes our two-part discussion on iterative and recursive asynchronous patterns. Thanks for reading.

Comments